Over the last few decades, the artist, Frida Kahlo has become one of the most recognizable women in the world, so much so, that the global obsession with her image has been described as ‘Fridamania.’

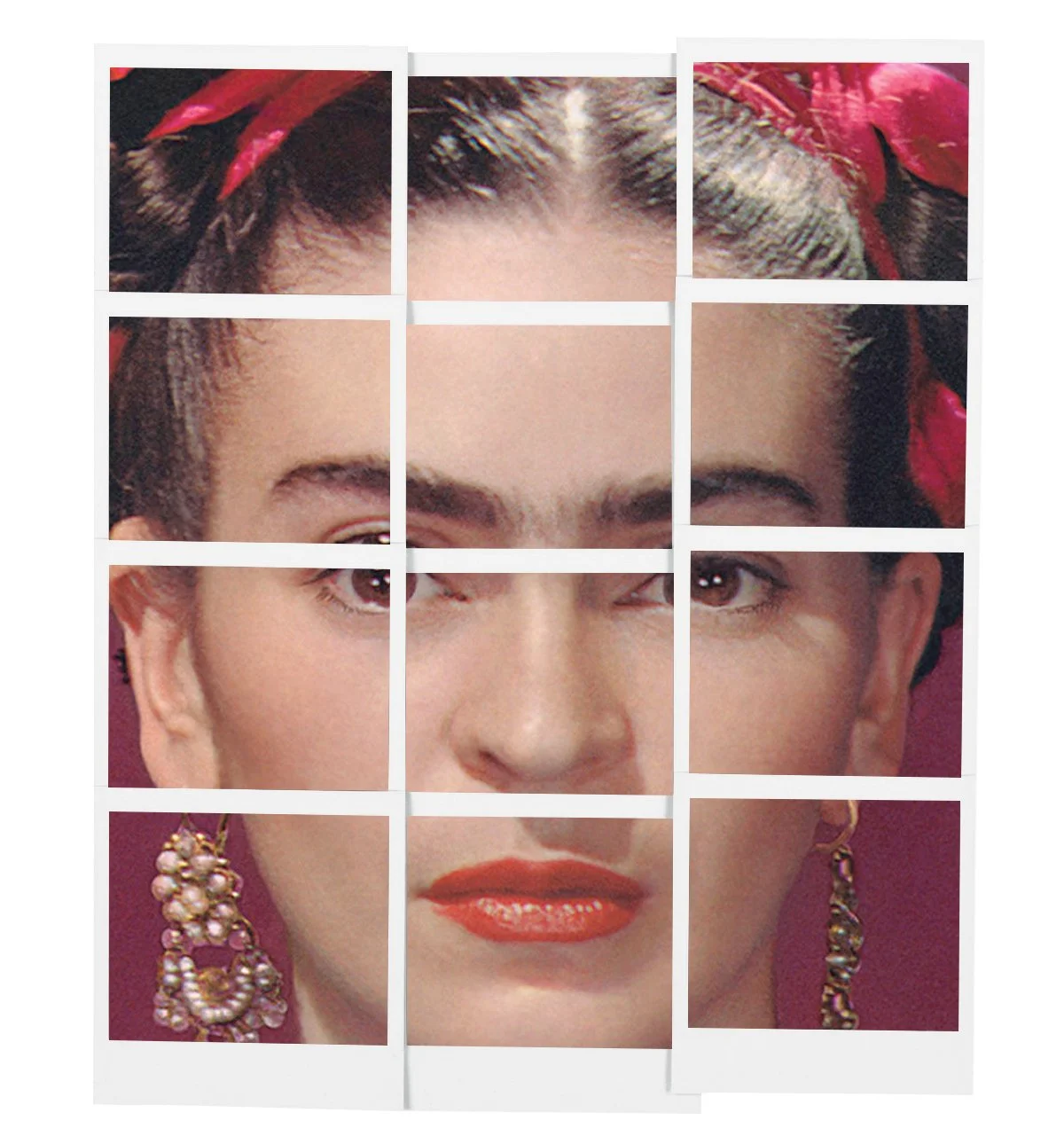

Her iconic look—dark hair dressed on the top of her head, braided with flowers and ribbons, emphasized monobrow, and bright red lips—has become so ubiquitous that a Professor at Harvard University turned ‘finding images of Frida Kahlo in your local community’ into an assignment for an online course. This fascination with the image of a woman who eschewed the established beauty ideals of her age, preferring to experiment and embrace her difference, is relatively new.

Not too long ago, in the 1990s, almost forty years after her death, her place in art history was a mere footnote, the third wife of a more celebrated artist, Diego Rivera.

The increase in interest in the life and work of Kahlo is typically attributed to the popularity of Hayden Herrera’s biography, Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo, first published in 1983, now translated into twenty-five languages, and the basis of the 2002 film about Kahlo starring Salma Hayek. The success of the book and film are echoed in two landmark exhibitions: The Whitechapel Gallery with Tina Modotti in 1982 and a solo exhibition at Tate Modern in 2005.

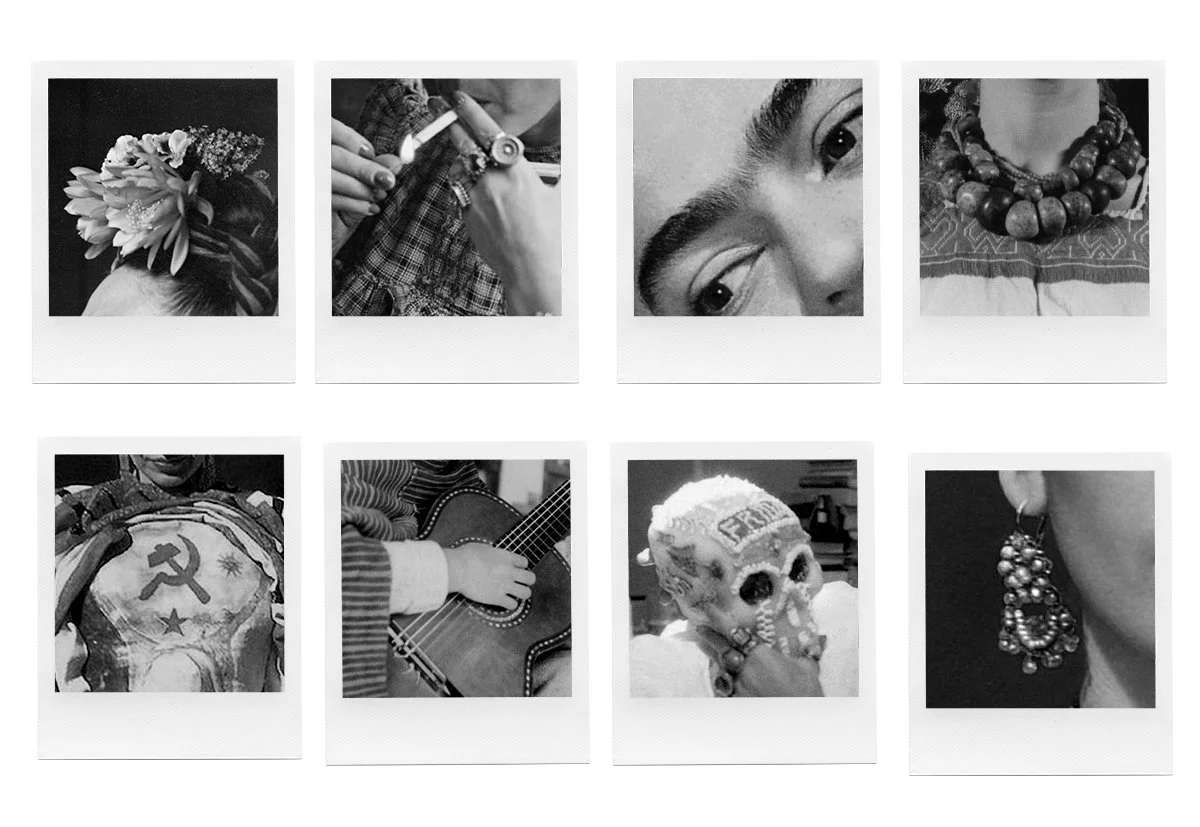

Image: Mary Zet

In her article, How Frida Kahlo became a Global Brand, Tess Thackara, connects ‘Fridamania’ with the rise of identity politics:

“Since her death in 1954, Kahlo has become a global symbol of resilience against adversity and patriarchal oppression, a feminist icon, and, thanks to her affairs with both men and women, a cult figure in the queer community.”

Kahlo’s image, now available on cushions, nail polish, jewelry, t-shirts, and widely referenced in fashion, has not just been popularized along with these political ideals, it has come to stand for them, but, as with any symbol, context is everything.

Last year, the British Prime Minister Theresa May wore a bracelet decorated with images of Kahlo during a speech at the Conservative Party conference leading to wide speculation as to what May intended to convey by publicly aligning herself with someone whose political views—Kahlo was a member of the Mexican Communist Party—differed so completely from her own. That no one could be sure what May was trying to say by quoting Kahlo’s image in her attire, serves as a useful reminder of the limitations of communication via the appropriation of images and symbols.

The careful curation of one’s image is not new; Elizabeth I, embraced it wholeheartedly when she styled herself the Virgin Queen in the 16th Century. Presenting such an otherworldly image long before the French sociologist Émile Durkheim would codify religious practices of separating the sacred (untouchable) from the profane.

Richard Hamilton’s screen print My Marilyn (1965), is based on photographs vetted and rejected (crossed out) by Monroe, illustrating how she controlled the construction of her image, but these photographs, which were first seen by Hamilton in Town magazine where they were published shortly after her death, also remind us of the limits of that control.

Images of all three of these women have been transformed into products and co-opted to convey messages that may not have aligned with their own beliefs, sometimes muddying and other times clarifying what these images mean, and what these women might have stood for.

The exhibition Frida Kahlo: Making Herself Up currently at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London suggests an alternative way to be inspired by and embrace Kahlo. Though the museum shop contains innumerable products sporting Kahlo’s face, the emphasis of the exhibition is how she created that iconic look. It is based on the discovery of a large cache of her personal belongings—clothing, shoes, jewelry, and make-up—that had been sealed in a room of the house she shared with Rivera since her death and only opened in 2004.

Despite the long catalog of objects on display, the emphasis is on process rather than products: this group of objects is only unified by the body that wore them, and only made coherent by the woman that chose them.

It is a collection so eclectic that it is most easily navigated in terms of opposing poles: traditional but contemporary, feminine but also masculine, comfortable and painful, sometimes beautiful, sometimes ugly. Prefiguring the quotation of her own image as a political symbol, Kahlo embraced traditional Mexican dress and jewelry but would wear it with contemporary makeup, like Revlon’s Everything’s Rosy lipstick and matching nail polish.

In her essay, in the exhibition catalog, Circe Henestrosa notes:

“The matriarchal society of the Tehuanas held a particular appeal for Kahlo, who was building her own image as an outsider: independent, but faithful to tradition, while at the same time embracing a modern, liberated lifestyle.”

Kahlo mixed local and global politics, painting the Russian communist symbol, the hammer and sickle, on the corsets she wore as a result of the road accident she was injured in as a young woman.

Henestrosa continues:

“Her adoption of this dress was conscious and considered, both distracting and purposeful: a complex combination of her communist ideology, her Mexican-ness, constructed from her personal traditions and as a reaction to her disabilities.”

This hoard of personal artifacts also reveals that her most recognizable feature, her monobrow, which she accentuated in self-portraits along with her mustache, was also something she emphasized in person; she owned both a Revlon eyebrow pencil in Ebony and Talika, a product used to encourage the growth of eyebrows and eyelashes.

Image: Mary Zet

The elements of her appearance that did not correspond to ‘typical’ ideals of feminine beauty were thus not just ‘endured’ but embraced, emphasized and encouraged. It is in those details that Kahlo differs significantly from Monroe and Elizabeth I. She had greater freedom than both the film star and the queen to invent herself, always carefully rejecting and selecting what she chose.

What this examination of Kahlo’s process reminds us, amid the increasing use of her image to sell both political views and an infinite variety of products, is that the freedom and creativity she stood for doesn’t reside in her image, but in her approach, her open mind, her firm beliefs, and willingness to experiment.